Midway Through Banff, Week 2

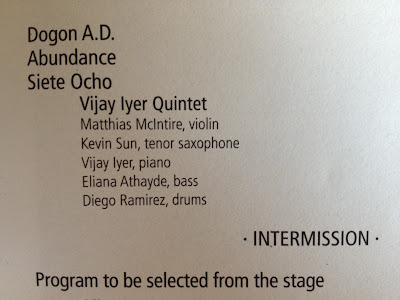

In the first week of Banff, Vijay Iyer presented a list of "bad binaries," i.e. , phrases or ideas that are often placed at odds with one another, but need not necessarily be. One such false opposition of ideas that came to mind today was the pairing of "subversion" or "disruption" of tradition with rigid adherence to tradition. A distinction should be made between negative terminology like "subversion" and "disruption"—which suggests replacement, destruction of established values, and the like—and the personal search for self-expression through personal and/or increasingly novel means. Liberty Ellman gave a masterclass today in which he emphasized the historical value of a tightly knit but broadly encompassing community in jazz, noting how musicians like Bud Powell who would come to influence musicians like Monk often were influenced later by those who they influenced. Sometimes, what comes across when somebody tries to do s