Sonny Rollins & Wilbur Ware on "I'll Remember April"

|

| The inscrutable gaze |

Returning to my conversation with Walt, he also said something that struck me as perceptive and sadly true, which is that bassists can sometimes get away with having a decent beat but plain boring lines (although we both conceded that sometimes lines that are "boring" or conventional, pitch-wise, are just so for the purpose of emphasizing the microrhythmically expressive and detailed aspects of the line). I asked Walt who he thought of as somebody with both an extraordinary beat and surprising choice of pitch, and the first person who came to mind was Wilbur Ware, whom Simón Willson (yet another close bass associate of mine and a Great On Paper compadre) had also repeatedly told me to check out, to no avail.

A Night at the Village Vanguard is one of those records that all jazz saxophonists have presumably checked out; for me, it's one that falls in the category of those records I feel I should definitely know way better than I do. Listening again with more attention to Ware, I felt immediately that these aren't just surprising note choices—they're thrilling and unceasingly inventive choices selected relationally with Sonny and Elvin, chorus after chorus. I also had the uncanny experience of hearing my close friends' playing reflected in this nearly 60-year-old recording, which, of course, is the actually experience of realizing the influence of a previously under-checked-out master on my friends' playing.

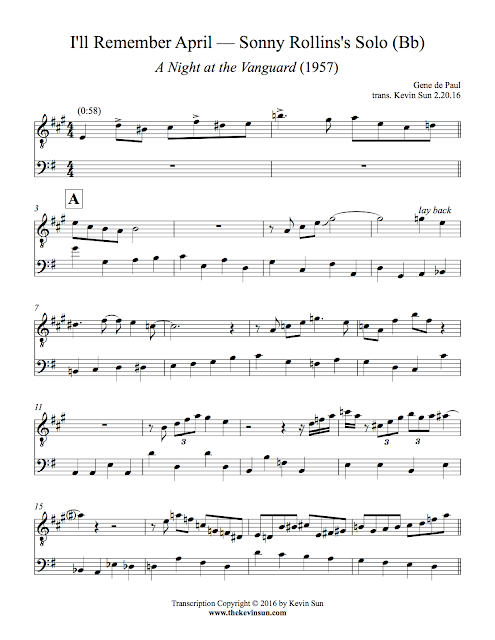

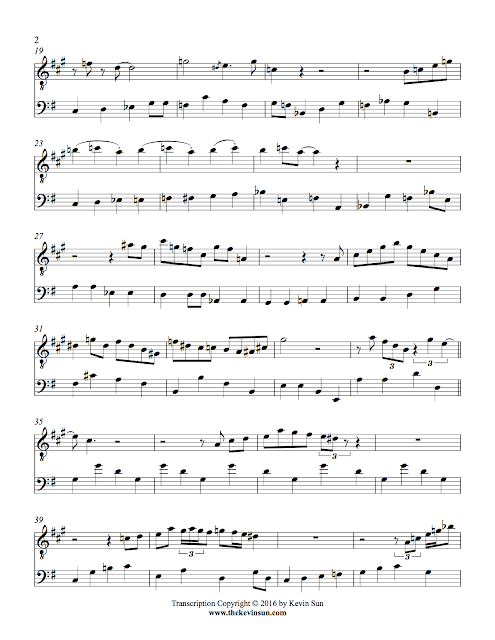

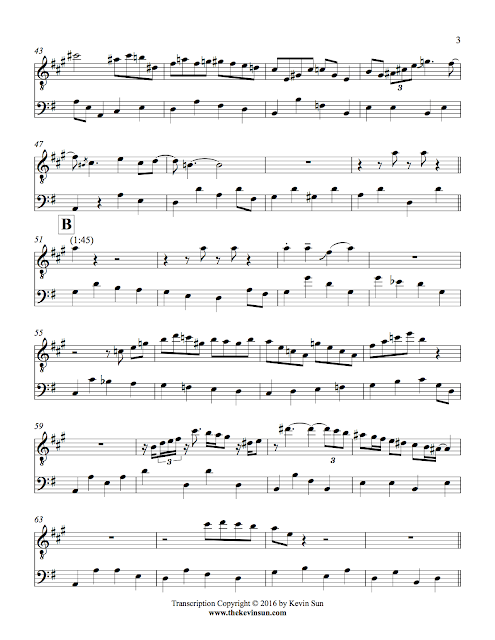

There's increasingly more and more appreciative material on Ware across the internet, including the Wilbur Ware Institute, this 2002 dissertation on Ware's playing (tl;dr—yet), a Do the Math blog post, and more. As a non-bassist, I marvel at the buoyant, at times seemingly reckless but unrelenting hook-up between Ware and Elvin on this record. There are countless moments of dramatic improvised synchronicity (the tops of the third and fifth choruses, where the long stretches of single tonal spaces are converted into rhythmically entraining interludes), slick voice-leading (the last five bars leading up to the fifth chorus), and microrhythmic detail (e.g., Sonny's initially seemingly unnotateable melody on the last A of the third chorus, which actually suggests a kind of subdivision when listened to slowed down, a lot).

Sonny Rollins & Wilbur Ware (Bb)

Sonny Rollins's Solo (Bb)

Wilbur Ware's Bassline (C)

* * * * *

On a distantly related note, I was pleased to gain a new appreciation of Ware upon rereading parts of George E. Lewis's seminal work on the AACM, A Power Stronger Than Itself, while TAing for Vijay Iyer's Music 173r ("Creative Music: Critical Practice Studio") at Harvard. Ware makes multiple cameos as an older, mentoring figure on the Chicago jazz scene. As bassist Leonard Jones recalls, Ware would get young bassists to dive straight into the action at sessions; a true sink-or-swim education:

"Usually what would happen is that Wilbur would introduce a 'young, up-and-coming bass player'—that didn't know no tunes," Jones laughed. "I'd have to go up and play after Wilbur played, on somebody else's gig." (79)Lewis importantly notes that autodidacticism, a hallmark of these creative improvisers, many of whom would ultimate develop unique, personal systems of music-making, wasn't necessarily a solitary, monastic practice, but one that was mediated by the community of musicians and listeners around them—learning by checking out older musicians in person and being around them. Malachi Favors did this firsthand:

"Wilbur couldn't really teach anything, because he didn't know how to explain," said Favors. "Even though he was one of the great bass players, he played, I guess, strictly by ear. But whatever he does, it was something else, so I just picked it up." (15)

Comments

Post a Comment